This photograph shows a detail from the official minutes of a meeting of the Air Officials Administration Conference which took place in the Air Ministry in London on the afternoon of 15 September 1943, about 15 hours after Lancaster JA981, piloted by Sqn Ldr David Maltby DSO DFC of 617 Squadron, had crashed into the North Sea. It is one of the three contemporary documents which each record that a collision had taken place between a 617 Squadron Lancaster and a Mosquito from 139 Squadron. (AIR 24/259, National Archives).

6,200 words/20 minute read

Back in 2008, in my book Breaking the Dams, I wrote an account of the last flight taken by David Maltby and his crew on the night of 14/15 September 1943. This RAF 617 Squadron crew was the same one which had flown on the Dams Raid in Lancaster ED906 AJ-J just four months earlier, when they were in the fifth aircraft to attack the Möhne Dam. They dropped the weapon which caused the dam’s final breach. For the September operation, targeted at the Dortmund-Ems canal, an extra air gunner, Wrt Off John Welch DFM, was added to the crew. The original account was based on my research at the National Archives in Kew and other sources, to which I was guided by Len Cairns (in whose debt I remain). This is an update of part of Chapter 9 of that book, with new information that has arisen since, in particular a previously unpublished navigator’s log kept by Sgt Wilfred Johnson, navigator in the 605 Squadron Mosquito piloted by Plt Off Arthur Woods, which was on attachment to 617 Squadron. The report was provided to me by Woods’s son, Allan, to whom I am very grateful for help.

I believe that the research indicates that there is a strong possibility that the fatal crash was caused by a collision between Maltby’s Lancaster and a Mosquito from 139 Squadron, returning to base after an attack on Berlin.

In early September 1943, 617 Squadron began preparation for its new role as a specialist low-level bombing unit. The first task it was given was to deploy the biggest bomb the RAF had yet carried in an attempt to breach another German key industrial target, the Dortmund-Ems canal.

The bomb was a new 12,000 lb thin-cased weapon, essentially three 4,000 lb bombs bolted together, with a six-finned tail unit on the end. It was fitted with a delayed action fuse, so that the bomber which released it would be away from the dropping zone before the explosion. The bomb was so big that it needed special trolleys to move it from the store and took 35 minutes to be winched up into the Lancaster’s bomb bay. They were delivered to RAF Coningsby, the home of the squadron since 30 August.

The Dortmund-Ems canal stretches over 150 miles, linking the Ruhr valley to the sea. At Ladbergen, near Greven, just south of the junction with the Mittelland Canal, there is a raised section where aqueducts carry the canal over a culverted river. This had long been a favoured target and had been attacked several times without success. The plan was to drop the new bomb from very low height into the soft earth embankments of the raised waterways.

The plan* was drawn up in great detail by Air Cdre H V Satterly, the Senior Air Staff Officer at 5 Group, and the man who had drawn up the final orders for Operation Chastise. The eight Lancasters detailed for the operation were to be accompanied by six Mosquitoes, specially brought in from 418 and 605 Squadrons. Their role was to deal with searchlights, flak and any fighter opposition met along the way or over the target. The force was to be divided into two sections of four Lancasters and three Mosquitoes each, with the force leader commanding the first section and the deputy force leader commanding the second. The two sections would fly out by separate routes, maintaining formation if possible, crossing the English coast at 1,500 ft and then dropping to 100 ft over the North Sea. The deputy force leader would arrive first, and mark the area with three special parachute beacons dropped on an exact grid reference. If they didn’t work, incendiaries were to be used instead. When all the Lancasters had arrived at the target, they would come under the control of the force leader, who would attack first. They were expected to drop their bombs in turn at a precise point within 40 ft of the western bank of the canal. The bombing height was to be 150 ft above the ground, at a speed of 180 mph. Once a breach had been caused, the aircraft were to drop their remaining bombs on alternate banks of the canal 50 yards further north each time until all the bombs were used up. The bomb fuses gave a delay of between 26 and 90 seconds, which was supposed to leave sufficient time for aircraft to get clear. The force leader was therefore supposed to ensure that at least two minutes was left between each aircraft’s attack.

* AIR 14/2038, No 5 Group Operation Order No. B66 dated 10th September 1943. (National Archives).

The 12,000 lb bomb they were going to drop was designed to take advantage of the Lancaster’s bomb-carrying capacity. As with the Dams Raid, the Lancasters had to be specially modified for the operation, this time with special larger bomb-bay doors, making the bay big enough to hold the enormous weapon. In this case, however, the mid-upper turret that had been removed for the Dams Raid was still available. Because the canal was known to be heavily defended, it was decided to carry a full-time front gunner on this trip, so an extra gunner was brought in for each aircraft to ensure that all three gun positions were filled.

The six Mosquitoes arrived on 5 September. Nearly every day afterwards they practised on co-operation flights with the Lancasters, which were still being modified. When the modifications were complete the Lancasters were tested out and then used on low-level bombing tests at Wainfleet. On one of these trips, on 9 September, David Shannon flew the aircraft David Maltby had started using, JA981 with the identification code KC-J, with William Hatton, Antony Stone, Victor Hill and Harold Simmonds from the Maltby crew on board. Also along for the ride were two from the Mosquito detachment from 605 Squadron, pilot Sqn Ldr Gibb and navigator Plt Off Mills. JA981 was a new aircraft, and had only arrived at 617 Squadron on 3 September. This was the aircraft Maltby would pilot on the night of 14 September.

By now, the two Davids, Maltby and Shannon, were close friends. David Shannon had become engaged to Ann Fowler, a WAAF officer attached to 617 Squadron, and they were due to be married on Saturday 18 September. David Maltby was going to be best man.

The raid was important enough to be given its own code name, Operation Garlic, and was scheduled for Tuesday 14 September. That morning George Holden asked Harry Humphries to draw up the battle order. Holden was to lead the first section of four, with Les Knight, Ralf Allsebrook and Harold Wilson. David Maltby would lead the second group: David Shannon, Geoff Rice and Bill Divall. Six Mosquitoes would fly with each section, three each from 605 and 418 Squadrons. The 605 Squadron detachment were piloted by Sqn Ldr Gibb, Flg Off Mitchie and Plt Off Woods, those from 418 Squadron were in the hands of Flt Lt Lisson, Flg Off Scherf and Flg Off Rowlands. As deputy force leader, David Maltby was due to drop the special parachute beacons which would mark the target.

The weather was not good, but it was decided to take off anyway. A separate Mosquito designed for meteorological work had already been sent to the target area and was due to report back. If it found that the weather was bad over the canal, then commanders could call the strike force back.

There is no doubt that the 617 Squadron crews knew how difficult this operation was going to be. They hadn’t flown over Germany since the Dams Raid almost four months before and in the run-up to the operation and at the briefing it must have been obvious that they were being asked to take part in another raid which would demand the utmost levels of skill and crew co-operation. Once again, they were using a brand new weapon, never before dropped in anger and, once again, they would have to fly to their target and attack it at an almost suicidally low height.

We can’t be certain how the Maltby crew lined up, but it’s likely that Vic Hill stayed in his Dams Raid position of the front turret, while the extra gunner, John Welch, took the mid-upper position. The rest of them would have settled down in their normal positions: rear gunner Harold Simmonds, wireless operator Antony Stone, navigator Vivian Nicholson, flight engineer Bill Hatton and bomb aimer John Fort.

There is a discrepancy in the documents about the time of take-off. One says it was 2329, another 2340. They set course for their crossing point on the Dutch coast, south of Texel Island. Then came the news from the Mosquito on weather-spotting duty. The target was badly obscured by mist and fog. At 0038, a recall signal was sent from the operations room at 5 Group in Grantham. And then, just as or just after, the recall signal was received, disaster struck and, somehow, Maltby’s Lancaster went down in the sea.

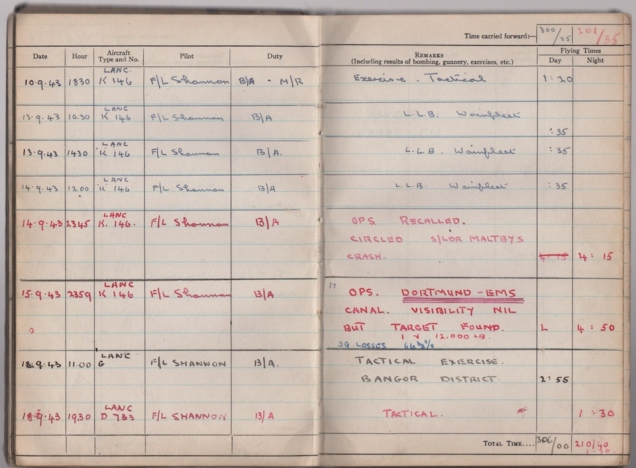

Accounts of how this accident occurred vary. For many years, it has been thought that the only surviving direct witness statements were in the logbooks of the Shannon crew, flying in the same section in EE146.

Shannon’s own entry reads in full:

Operations – Dortmund Emms [sic] Canal. 1 x 12,000. 4 incends. (90×4). 2 marker beacons. Recalled weather u/s. Jettisoned. S/L Maltby crashed in sea. All killed. Directed Air Sea Rescue launches which arrived in about 1 ½ hours. Circled 3 hours in touch with 5 Group.

Total flying time: 4.15

(Shannon logbook, photocopy in IWM collection)

It’s a very bald account of the death of a close friend. Now he needed a new best man for his wedding, and it was only four days away.

The accident is also recorded in at least two of the logbooks of Shannon’s crew, wireless operator Brian Goodale and bomb aimer Len Sumpter.

Goodale’s entry reads:

Ops recalled. Carried out sea search for ‘J’ (S/L Maltby D.S.O. D.F.C. killed)

(Goodale logbook, Goodale family collection)

Sumpter’s account is even briefer:

Ops recalled. Circled S/Ldr Maltbys crash.

(Sumpter logbook, Sumpter family collection)

Neither of Shannon’s crew’s entries add any further information about the accident. However, another direct witness’s account has now been sent to me. This is from the navigation log kept by Sgt Wilfred Johnson, the navigator in Plt Off Woods’s Mosquito, HJ785 UP-T.

(Sgt Wilfred Johnson navigation log, Woods family collection)

The relevant section reads:

00.30 Formation told to return to base.

00.31 A/c (S/Ldr MALTBY) in flames dived into sea. Called “MAYDAY”.

‘G’ Fix obtained 53°04 N, 01°53 E over wreckage.

01.45 A.S.R. Launch and A/C on scene of accident.

01.50 Returning to BASE s/c 281 M.

Johnson would have written each entry onto his notepad as it happened and he definitely saw the aircraft ‘in flames’. Shannon’s logbook entry – obviously written after he had got back to base – is interesting for what it doesn’t say. For instance, there is no mention of turning or catching another aircraft’s slipstream. This would suggest that he did not see the crash directly, but surmised it afterwards. The question should also be asked of both about how much would either have been able to see directly at night in poor weather conditions? It is not known whether Johnson and his pilot Woods were debriefed by intelligence officers after they landed, but presumably they must have been. It should also be noted that Johnson recorded the arrival of a rescue aircraft, although there is no mention in official records of one being dispatched.

Left, Sgt Wilfred Johnson and, right, Plt Off Arthur Woods, witnessed the crash of David Maltby’s Lancaster on 15 September 1943. (Pic: Woods family collection.)

Other official documents and other contemporary accounts tell a slightly different story, and have a number of significant variations. What was probably the next chronologically appears in the ‘operation summary’ section of the 617 Squadron Operation Record Book. This would have been written by the Squadron Adjutant, Harry Humphries. It reads:

… At approximately 0040 hrs, on the 15th, a recall message was sent to all aircraft, on account of unfavourable weather. The aircraft were then over the North Sea, and in turning to make the homeward journey the aircraft piloted by S/Ldr Maltby was seen to crash into the sea. Nothing definite is known of the cause of this accident, but it is possible that the aircraft struck the water. The crew was as follows: S/L D.J.H. Maltby D.S.O., D.F.C., Sgt. Hatton (F/E), F/Sgt. Nicholson D.F.M. (Nav.), F/Sgt. Stone (W/Optr.), F/O J. Fort D.F.C. (A/B), W/O Welch (M/G), F/Sgt. Hill (F/G) and Sgt. Simmonds (R/G). F/Lt Shannon circled over the spot for over two hours and directed the Air Sea Rescue service to the scene. The body of S/L Maltby was recovered, but no trace was found of the remainder of the crew.

AIR 27/2128, 617 Squadron Operations Record Book

Harry Humphries also wrote a more personal account in the unofficial notes he was making for his own reference. He was already planning to write a book about the squadron after the war, although circumstances meant that it wasn’t actually published until almost sixty years later. There are more than twenty pages of a draft in a loose-leaf folder in Lincolnshire County Council archives, and many more still in his family archive. The pages in the council archives are not dated but are known to have been written in September 1943. This is what he wrote:

Then came disaster of the first order. Our ever popular S/Ldr ‘Dave’ Maltby crashed into the sea, and his body was picked up by rescue launch a short time after. Of the other members of the crew there was no trace. F/Lt Shannon carried out sterling work here, and circled around over the scene of the accident for 2 ½ hours directing A.S.R.B. to the place. This was indeed a black day for us, and even though the boys tried hard not to show their feelings – there were very few smiles.

Harry Humphries, Manuscript Notes, Lincolnshire County Council Archives

These two pieces written by Humphries are important sources, because he recorded what was known at Coningsby that night. He notes both that rescue launches had arrived, and that one had recovered a body. In his 2003 book he goes a little further:

Within an hour we received news that our machines were returning to base because of unfavourable weather conditions and, worst of all, one of them had crashed into the sea off Cromer. All was confusion for some time. The Lancasters began to land at Coningsby and garbled reports on the ill-fated aircraft began to circulate.

Eventually the truth became apparent. Our own Dave Maltby had gone. By some wicked stroke of misfortune he had hit the sea and in spite of very good work by Brian Goodale, Shannon’s wireless operator, only one body, that of Dave Maltby himself, had been found by the Air Sea Rescue launch.

Harry Humphries, Living with Heroes, Erskine Press 2003, pp65-66

This account immediately begs the question: what could the “garbled reports” have said?

There are also other official accounts. Every unit of the RAF, from a squadron upwards, has its own Operations Record Book, which means that an incident like this was recorded in other places. The first of these is the record book for 617 Squadron’s station, RAF Coningsby. Its report differs slightly from the version found in the squadron’s record:

… Owing to weather conditions, the formations were recalled at 0030 hrs. Shortly after receiving the recall, the majority of a/c observed a terrific explosion on the sea. This is presumed to be S/Ldr Maltby who failed to return.

AIR 28/171, RAF Coningsby ORB.

The slight variations in times are probably not too significant, but what is interesting is that the account is curiously vague about who, other than Shannon, ‘observed’ the explosion. It is also the first document to mention an explosion. A week or two later a formal Accident Card was prepared by a small panel, or perhaps even just one officer. The panel would have considered the information sent in by the squadron in writing and then summarised its findings.

Form 1180, accident card, JA981, September 1943. lancasterbombers.net (courtesy Dominic Howard)

This is transcribed below:

Time: 0045. Ops night. Recall to base.

A/c missing. Presumed hit sea. Invest[igators] consider the accident was due to the a/c hitting the sea after some obscure explosion and fire had occurred in the aircraft. It is possible that the pilot partially lost control in a turn when bomb doors were opened to jettison bombs. Explosion and fire may have been caused by bouncing on the water. None of the equipment likely to have exploded in the air.

Aoc cause obscure.

Aoc i/c [?Air Officer Commanding in charge?] only E/A [enemy aircraft/action] could have set bombs or incendiaries on fire in the air. NB Large bomb doors affect a/c’s stability when lowered.

[Conditions] Night, moon, dark.

There is another mention in the RAF Coningsby ORB. At the end of each month, the medical officer would write an appendix detailing important medical ‘events’ which had occurred in that time. Although he does not appear to have been directly involved in the incident, he saw fit to include it amongst the accounts of bomb store accidents and football injuries:

14.9.43. One aircraft from 617 Squadron reported to have crashed in the sea – S/Ldr. Maltby and crew. Body of S/Ldr. Maltby was recovered from the sea and taken to R.A.F. Coltishall. Death was due to multiple injuries.

AIR 28/171, RAF Coningsby ORB.

So we apparently have ten contemporary or near-contemporary accounts, four from witnesses who were in the air at the site of the crash.

It was these sources which formed the basis for the narrative in Paul Brickhill’s book The Dam Busters, published in 1951. He wrote:

They were an hour out, low over the North Sea, when the weather Mosquito found the target hidden under fog and radioed back. Group recalled the Lancasters and as the big aircraft turned for home weighed down by nearly 6 tons of bomb David Maltby seemed to hit someone’s slipstream; a wing flicked down, the nose dipped and before Maltby could correct it the wing-tip had caught the water and the Lancaster cartwheeled, dug her nose in and vanished in spray. Shannon swung out of formation and circled the spot, sending out radio fixes and staying until an air sea rescue flying boat touched down beneath. They waited up at Coningsby till the flying boat radioed that it had found nothing but oil slicks.

Maltby’s wife lived near the airfield, and in the morning Holden went over to break the news, dreading it because it had been an ideally happy marriage. Maltby was only twenty-one. The girl met him at the door and guessed his news from his face.

‘It was quick,’ said Holden, who did not know it was his own last day on earth. ‘He wouldn’t have known a thing.’

Too stunned to cry, the girl said, ‘I think we both expected it. He’s been waking up in the night lately shouting something about the bomb not coming off.’

Paul Brickhill, The Dam Busters, Evans Brothers 1951, pp.117-8

We can guess that Brickhill must have derived this account from talking to David Shannon, and perhaps also wireless operator Brian Goodale, who between them directed the air sea rescue launches to the site while their aircraft circled above. Brickhill was a journalist, not a historian, and as usual, he relied on accounts from eyewitnesses recalled several years later without looking at any primary sources. (To be fair to him, it should be pointed out that many of these sources were still classified under the 30 year rule, and therefore did not become available until the 1970s.)

There are several inaccuracies in Brickhill’s account: Maltby was 23, not 21. The air sea rescue service sent two launches, not a flying boat, and one of the launches recovered Maltby’s body. There was no trace of the rest of the crew.

It is now that Len Cairns comes into the story. I had first heard his name in 2007 from the family of Vivian Nicholson, navigator in David Maltby’s crew. They had told me that Len had written to them about this final crash, and sent them some pages from the typescript of a book he was writing. When I got round to ringing him a few weeks later, he told me an astonishing story.

Simply put, there was a good chance that an errant Mosquito, flying low on a return from an attack on Berlin, crossed paths with the 617 Squadron section and collided with Maltby’s Lancaster. Most people had previously discounted this theory since the six Mosquitoes seconded to the mission from 418 and 605 Squadrons all returned safely. However, they all seem to have overlooked other material turned up by Len Cairns in the National Archives.

This backed up a claim that I had heard mentioned before, made by Maltby’s uncle, Aubrey Hatfeild, who had been an RFC pilot in the First World War. Sometime after the crash he told his sister Aileen, David Maltby’s mother, that his Lancaster had been struck by a Mosquito ‘which shouldn’t have been there’. Hatfeild was apparently adamant about this: it was not an error made by Maltby in turning the aircraft, or of hitting someone else’s slipstream. ‘He was too careful a pilot to have made an elementary error,’ he often told his own children. One of them, Mary Tapp, relayed this information to me when I started researching my book.

It’s not clear however where Aubrey Hatfeild may have got this information. But it does turn out that, away from Coningsby, there were contemporary reports that a collision had occurred.

The evidence for this is buried deep in the files held at the National Archives. The first clue is in the Operations Record Book for 278 Squadron. This was the Coastal Command squadron which was responsible for air sea rescue in the Norfolk coastal area. Based at RAF Coltishall, about eight miles north west of Norwich, it flew Ansons for general searches and a Walrus flying boat for picking up ditched aircrew. The Air Sea Rescue launches from 24 ASR at Gorleston, which were directed to the crash by David Shannon’s aircraft, were also administratively attached to the RAF Coltishall station. The 278 Squadron ORB records that an Anson was sent out at 0638 on the morning of 15 September from Coltishall to search for a Lancaster and Mosquito ‘reported to have collided’. The full entry reads:

A/C ANSON No EG496

CREW

F/O SIMS, W F

F/Sgt HAMMOND, A

F/O DUNHILL, A

F/O RICHARDSON, K

W/O FRASER, R D

DUTY: Search position H.0374 for Lancaster and Mosquito reported to have collided.

TIME OF SEARCH: 06.38 – 07.56 hours.

Aircraft searched this position and found an oil patch approximately one mile long and 200 yards wide in which were small pieces of wreckage. Nothing further was seen and a ‘fix’ was transmitted to operations after which A/C returned to base.

AIR 27/1605, 278 Squadron ORB.

The squadron’s entry is corroborated by a similar entry in RAF Coltishall’s own Operations Record Book:

An Anson 278 Squadron was up 0638-0754 to search for wreckage of a Lancaster and a Mosquito which had collided during the night. A large oil patch one mile long and 200 yards wide was found approximately 53°05 N, 01°41 E, and though this was circled for 20 minutes, only small pieces of wreckage were seen. The Anson then returned to base in very bad weather.

AIR 28/168, RAF Coltishall ORB.

It’s worth noting here that on 15 September 1943, with summer time still in operation, 0638 would have been not long after first light. The accident happened at about 0040, in the dark and in bad weather conditions. So at some time in the night, somebody in a senior position at Coltishall had been told that the accident was caused by a collision and had been requested to make a search at dawn.

Later that day a report had reached London. Every afternoon a group of senior officers would convene in a meeting room at the Air Ministry to discuss technical and administrative matters concerning Bomber Command. It was called the Air Officers Administration Conference (usually abbreviated in the files as the AOAs Conference). They would note details of the numbers of squadrons available, the ferrying of aircraft to and from different stations and the mechanical and other problems that had occurred. But they also looked at the numbers of operations flown, the losses incurred and, particularly, since they were interested in ironing out any repeated mechanical failures, which might be the cause of crashes. That very day, probably within 15 hours of the incident occurring, they noted that there had indeed been a crash the night before. The minutes of the conference state, quite baldly:

Crashed:

1 Lancaster of 617 Squadron and 1 Mosquito of 139 Squadron are believed to have collided N.E. of Cromer. No survivors yet reported.

AIR 24/259, AOAs conference, No 258, 15 September 1943

Back in 2007, when Len Cairns read this extract out to me over the phone I could hardly believe it. ‘You mean that the other aircraft can actually be identified?’ I asked. ‘Yes, it can’, Len replied. It was one of a group of eight from 139 Squadron who had been despatched on a ‘nuisance raid’ over Berlin. One Mosquito, DZ598, had been recorded as ‘did not return’, as nothing had been heard from it after it took off from Wyton in Cambridgeshire at 1936 hours on 14 September. The pilot was Flt Lt M W Colledge and the navigator Flg Off G L Marshall.

The 139 Squadron records are not very informative. The RAF Wyton ORB gives a little more detail about the raid:

This trip was made unusually difficult by heavy cumulonimbus, which caused several crews to return early and made the operation longer and more arduous for those who pressed on to the target.

F/L Colledge did not return; nothing was heard of him after take-off.

S/Ldr Braithwaite, F/O Mitchell and F/O Patient attacked Berlin in face of searchlights and moderate heavy flak.

S/Ldr Braithwaite received a Pasting from Brandenburg where he was coned for 10 minutes, and hit in eight places, though none serious.

Faced with the cumulonimbus, F/O Jackman attacked Emden and F/O Swan attacked Borkum Aerodrome, by D.R. Technique, with unobserved results.

F/Sgt Wilmott and F/Sgt Marshallsay returned early having iced up in cloud and decided that they could not get through.

AIR 27/960, RAF Wyton station ORB

The 139 Squadron ORB has a similar entry, with the added information about the weather in the North Sea: ‘severe thunderstorms and heavy Cu-nim [sic] with some icing was encountered near the Dutch Coast’.

AIR 28/963, 139 Squadron ORB

There is no further information about what happened to Flt Lt Colledge’s Mosquito. As nothing had been heard from him after take-off, and no wreckage was ever found, it has always been assumed that he was lost over the sea on the outward trip. Len Cairns’ theory is that his radio failed, but he decided to press on to Berlin regardless. On the way home, his aircraft collided with Maltby’s.

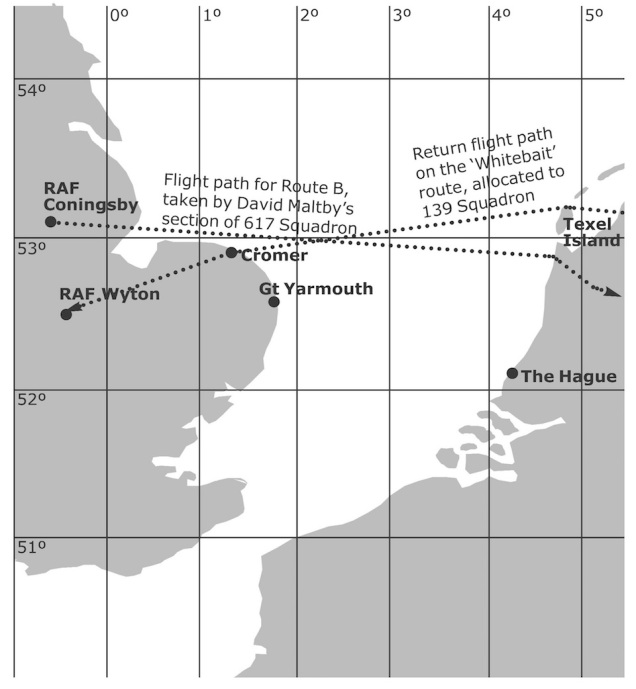

It’s certainly plausible. If Colledge had gone onto Berlin, he would have been coming back across the North Sea between 0030 and 0100, and his route from the northern end of Texel Island off the Dutch coast to landfall at Cromer would have intersected with the 617 Squadron Lancasters’ route, which was due to take them from Coningsby to landfall on the Dutch coast just north of Petten. Plotted out on a map, the intersection point is very close to where we know the accident occurred.

Map showing the route B allocated to David Maltby’s section of four Lancasters from 617 Squadron and their Mosquito escorts. They were ordered to fly directly from Coningsby to landfall on the Dutch coast a little way south of Texel island. The 139 Squadron Mosquitoes tasked with attacking Berlin were allocated to the ‘Whitebait’ route, the return leg of which runs from the northern end of Texel island to landfall at Cromer. The two routes intersect very close to the the point where Maltby’s Lancaster crashed into the sea. (Artwork by Charles Foster).

Would Colledge have flown on to Berlin, even if his radio had failed? His background certainly suggests that he had the ‘press on’ attitude so beloved of senior RAF commanders. His full name was Maule William Colledge, and he was the elder of the two children of the distinguished throat surgeon Lionel Colledge. He had been in the RAF since the beginning of the war. He was known for his love of fast cars and flying, and once had a single seater plane at Brooklands aerodrome for his own use. His sister Cecilia also had an interesting career: she was a figure skater and competed in the 1932 Winter Olympics held in Lake Placid, USA at the age of 11 years and four months. She remains the youngest ever British Olympian and went on to win a silver medal at the Winter Olympics, held in Garmisch-Partenkirchen, Germany, in 1936, at the age of 15. She died in 2008. Little is known about the Mosquito’s other crew member, its navigator, Flg Off Geoffrey Marshall, who was 30 and came from Brighton.

So we have three separate statements that there was a collision between a Lancaster and a Mosquito, one of which mentions the squadrons involved. Another piece of evidence would surely be that of the ORB for the Air Sea Rescue unit which operated the launches. Maddeningly, this doesn’t appear to have been preserved. At the time, responsibility for Air Sea Rescue was in the process of being passed from the navy to the RAF, and all the RAF records start just a couple of weeks later, on 1 October 1943. There are very detailed records for individual search and rescue operations from that date onwards – but none from before.

This makes it very difficult to work out how information about a possible collision reached the Air Ministry and, indeed, what made someone there cite the squadron numbers at the AOAs Conference. Did they have some other evidence or, because there had been a report of a collision between a Mosquito and a Lancaster, and only one of each type had been lost on the night, did someone just assume that these were the aircraft and squadrons involved?

It should be said that the collision theory can only be supposition. There is absolutely no evidence that Colledge got as far as Berlin, and then decided to fly back at low level. If he did, without a working radio, he would have put himself in danger of being mistaken for a Luftwaffe intruder and being shot down. The ‘collision’ entries are from documents written up immediately after the incident, and may have arisen because reports of both a missing Lancaster and a missing Mosquito were misunderstood as a collision between the two by the dispatchers of the Anson search aircraft. It is even possible that the person who compiled the official Accident Card knew about this theory and discounted it when he wrote up the card a few days later.

Maule Colledge, photographed by Bassano Ltd on 23 November 1936. National Portrait Gallery collection, number 104533. [Pic: NPG/Creative Commons 104533.]

Supposition it may be, but what is clear is that no one at 617 Squadron knew anything about a Mosquito being involved. Neither Shannon nor anyone from his crew ever said anything of the kind to John Sweetman, Robert Owen or others they spoke to over the years. However, they would not have denied, as Harry Humphries noted in his account, that there was a certain amount of confusion on the day. Also, it was dark and the weather conditions were poor. How much could they actually see? Nor was there much chance for further reflection on the circumstances of Maltby’s crash because the squadron suffered an even bigger disaster in the next 24 hours. The seven crews that returned safely to Coningsby in the early hours of 15 September flew back to the Dortmund Ems canal that night, with Mick Martin taking Maltby’s place. In very bad weather conditions they failed to damage the canal, and five aircraft were lost. Four complete crews and Les Knight, pilot of the fifth plane, were killed. (Knight’s crew baled out while Knight struggled to keep his damaged aircraft aloft. They all owe their lives to him.) George Holden, the squadron’s new CO, was one of the men lost that day, and in his crew were four of the men who had flown with Guy Gibson on the Dams Raid. It would be understandable that in these terrible circumstances that no one sought to find out more about Maltby’s crash, and relied on what they had been told.

There are some other mysteries about the night of 14/15 September. The RAF Coltishall account states that Maltby’s body was recovered and taken to RAF Coltishall. If this was the case, then Coltishall’s Medical Officer should have recorded this in his monthly appendix to his station’s ORB, since he was responsible for the station’s mortuary. Like his counterpart at Coningsby, the MO was a fairly assiduous record keeper. His September 1943 report contains accounts of a number of other incidents on the station, but there is nothing about Maltby. In fact it is likely that his body might never have reached Coltishall. According to Tony Overill, whose father served in 24 Air Sea Rescue, and who has himself written a history of the Unit, Crash Boats of Gorleston, bodies recovered at sea were taken to the civilian mortuary at Great Yarmouth, which was close to the harbour. He thinks that it would be very unlikely that it would then have been taken from there to Coltishall.

Also, it is not clear exactly how Maltby died. The MO at Coningsby states that the cause of death was ‘multiple injuries’. This would have been likely if there had been some sort of explosion on board. However, his widow Nina told her daughter Sue, many years later, that when she saw his body there was only a small bruise on his forehead, and no other obvious marks at all. This suggested to her that he had been knocked unconscious, and died from drowning.

As we have seen, and it is confirmed by Humphries, George Holden called over to see Nina in Woodhall Spa on the morning of Wednesday 15 September, to tell her what had happened. Paul Brickhill’s account of their conversation (see above), where he doesn’t even give her a name, may not be accurate, because it is difficult to see how he sourced it. It was, as he says pointedly, Holden’s own ‘last day on earth’.

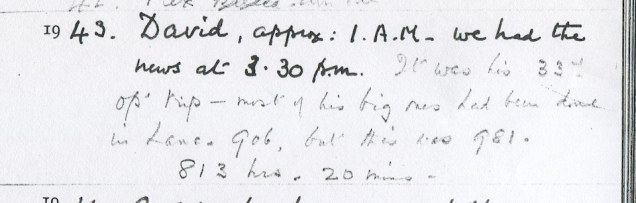

Later that day in Devon, David’s parents, Ettrick and Aileen Maltby, got the news, probably by telephone from Nina or her family. Ettrick wrote a bald entry in his diary:

15 September 1943: David, approx: 1 A.M. – we had the news at 3.30p.m.

This was written in a blunt, dark pencil. Then underneath, in a lighter pencil:

It was his 33rd op. trip – most of his big ones had been done in Lanc. 906, but this was 981.

813 hrs–20mins.

He can’t have known these details on the day of the crash, but he was right. As we have seen, David Maltby was flying in a new Lancaster, JA981. His Dams Raid aircraft, Lancaster ED906, call sign AJ-J, must have been a lucky plane as it survived the war and was eventually scrapped in 1947. Lancaster JA981 had only flown for 41 hours before it crashed. In 2006, when I first read this entry, I puzzled over how and when Ettrick had managed to get hold of the serial numbers of his aircraft, let alone the total number of hours he had flown in his RAF career. I later realised that he must have copied this information from his son’s logbook, and added it to his earlier diary entry.

By the time his parents were informed, David Maltby along with John Fort, William Hatton, Victor Hill, Vivian Nicholson, Harold Simmonds, Antony Stone and John Welch had all been dead for some 15 hours, and the telegrams were on the way. Four days later, Maltby was buried in the graveyard of St Andrew’s church in Wickhambreaux, Kent, the same church in which he had got married sixteen months before. The remainder of his crew, whose bodies were never recovered, were listed on the Runnymede war memorial, unveiled by the Queen in 1953.

Seventy-eight years later, we salute them all again.

Thanks to Allan Woods, Robert Owen, Dominic Howard and Len Cairns for help with this article.

Copyright © Charles Foster/Dambusters Blog 2021.

An earlier version of this piece was first published in my book Breaking the Dams (Pen and Sword, 2008).

Further information:

Aircrew Remembered page about Maule Colledge and Geoffrey Marshall

As ever, a brilliant piece of research, Charles. Thank you.

Very interesting read Charles , great article uncovering this new info. I don’t think we came across any of this while working on our books. (Chris Ward and I )

Harris and Speer were correct with regard to the failed Operation Chastise.

Had Harris followed the raid up it might not have been “failed.”

Aerial reconnaissance showed a follow-up raid would be suicidal.

It’s literally laughable to claim that a follow on raid would have been suicidal. High altitude dropping incendiaries would not have been any more suicidal that any other Ruhr raid and would have caused a lot of damage – the dams were festooned in wooden scaffolding and fire does a lot of damage to masonry.

Speer had installed far more anti-aircraft guns and defences.

Chastise was a war crime which achieved nothing, as Harris admitted in January 1945.

This is fascinating, really well researched information adding new light to the topic. Many thanks.

Thank you, brilliant, never fails to stir the heart.Sent from my Galaxy

Great research Charles – It must have taken a while to put it all together but it really adds to the story of your uncle.

Dear Charles

An excellent blog and thank you very much for such an informative piece about poor David Maltby and crew.

A couple of things that I picked up on, if you don’t mind.

1. In Goodale’s Logbook he records that he flew EEHG on 9/9/43 but in fact I believe he flew in JA981 that day with Shannon, or is it that he flew with another pilot in EEHG and erroneously recorded that Shannon was his pilot in EEHG

2. You mention that Johnson noted the “arrival” of a rescue a/c, but I think the a/c he recorded was Shannon’s which of course was already on the scene and would remain there for 2-3 hours. That’s why there is no record of a a/c being dispatched.

Again, thank you for such a brilliant blog, I enjoy receiving them and learning more about the crews of 617.

Best wishes

Paul

Paul White

Hi have you any information on Thomas Alfred Meikle on the same mission

Get Outlook for Android

________________________________

An absolutely brilliant, fascinating and informative article.

Any information on norman burrows? Thanks